Delta, Breakthrough Infections, and Waning Immunity

In the Delta-driven pandemic, the usual rules don’t seem to apply.

Where do things stand with the pandemic? It’s easy to lose track what with summer setting in and other events in our life taking precedence, to say nothing of reporting fatigue and the speed at which circumstances on the ground can shift. But things are not looking particularly rosy in the U.S. right now. Covid-19 isn’t roaring back exactly, but Delta is certainly making its presence felt across the country. After passing 35 million reported cases and 615,000 reported deaths and counting, you might be wondering: is the worst behind us or still to come? The answer, it turns out, could depend on where you live.

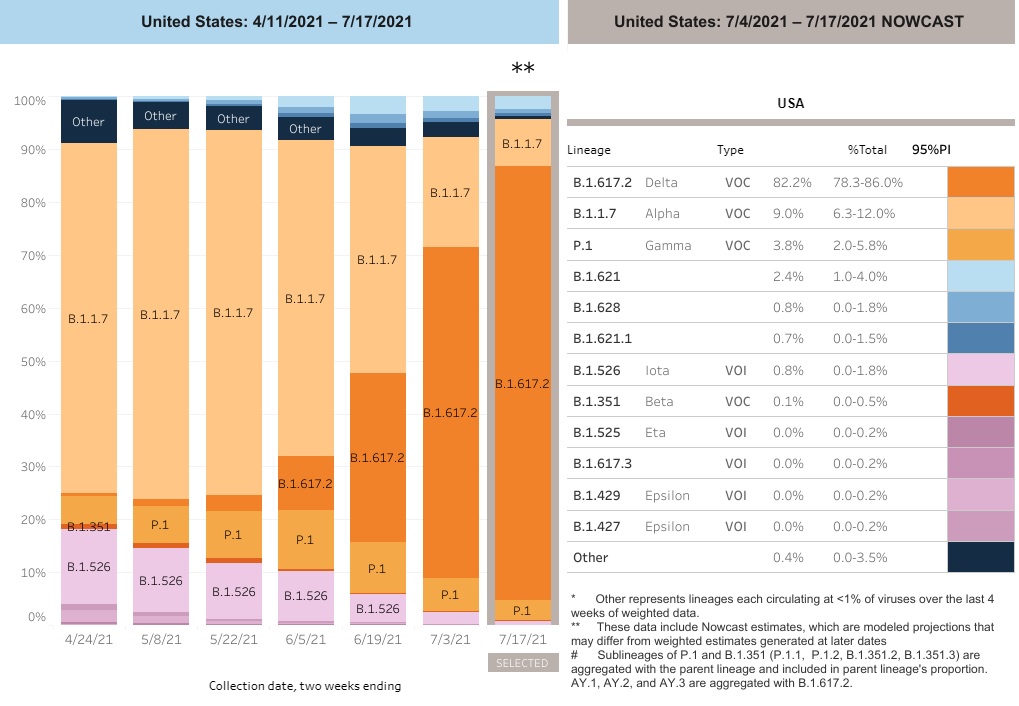

The Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, you may recall, was first identified in India last October. With some haste it managed to outcompete all rivals, including previous Big Bad Alpha, the variant discovered in the UK in December. After dominating the world in early 2021, Alpha ebbed away and the faster-spreading Delta variant swept across the globe. In the U.S., Delta first took the lead toward the end of June, and now makes up around 82 percent of all collected sequences. One month ago, it made up a third of all cases in the country, giving you a sense of how quickly Delta’s jumped ahead. It is now the motive force behind the pandemic, without which all relevant research and reporting is incomplete.

Of all the variants that have come before, Delta is also the most worrisome in essentially every category that matters. It’s at least 40% more transmissible than Alpha and twice as transmissible as the original coronavirus. Its incubation period is two days shorter on average, meaning people can begin shedding the virus that much earlier after exposure, and it’s capable of generating viral loads up to 1,260 times higher than the original strain. And perhaps most concerning, our vaccines appear to be less effective against Delta at blocking infection — though they remain exceedingly effective at keeping you out of the hospital. The jury is still out on whether Delta is inherently more deadly or likely to cause severe disease in unvaccinated individuals, but initial data from the UK isn’t reassuring.

None of this is surprising from an evolutionary point of view, as natural selection tends to favor transmission and vaccine escape. Any contender hoping to elbow out the defending champ must perform better in at least one of the above areas. Delta might hold the crown for now, but unless we do more to arrest its spread (read: more vaccines in more places), a more formidable challenger will inevitably emerge to take its place.

Low Vaccination Rates

States lagging behind in vaccinations are prime targets in Delta’s relentless pursuit of viable hosts. In Louisiana and Missouri and Arkansas and Mississippi and Tennessee, the virus is currently having a field day. We’re seeing the largest case spikes in rural counties that have been relatively untouched to this point. And because rural America has a considerable vaccine hesitancy problem, an avoidably high number of those infected will lose their life to Covid-19. In fact, virtually all hospitalizations and deaths at this point involve unvaccinated persons.

We saw similar surges last year, in which a single superspreader event could effect chains of transmission that overwhelmed small towns — same song, second verse. But due in part to the heightened transmissibility of the Delta variant, and the large number of holdouts refusing the vaccine, many states could actually experience more suffering at the local level in 2021 than in 2020.

Yes, that’s as scary as it sounds. Or at least it should be, especially for the unvaccinated, but also for health care workers anticipating overburdened facilities as Covid-19 gains a foothold in their community. Rural hospitals often have limited resources, such as beds and ventilators, both of which can dwindle quickly during a pandemic. In southwestern Missouri, it’s being reported that a hospital in Greene County is busier now than at any point since the pandemic began. In Florida, hospital admissions in Jacksonville and Brevard County are soaring past the peaks of last summer.

I suspect we’ll see a familiar story arc play out over the next few years. Delta — and Delta 2.0, along with other subsequent variants — will continue to burn through unvaccinated populations like wildfire until there are too few receptive hosts for the virus to self-perpetuate. As communities approach herd immunity, a phenomenon in which a sufficiently immunized population breaks the chain of transmission, daily case numbers will trend back down, with occasional flare-ups in more isolated communities that the virus hadn’t managed to breach in the past. Eventually, enough people will have either been vaccinated or infected that the virus struggles to carry on (unless of course immunity begins to wane; more on this possibility later).

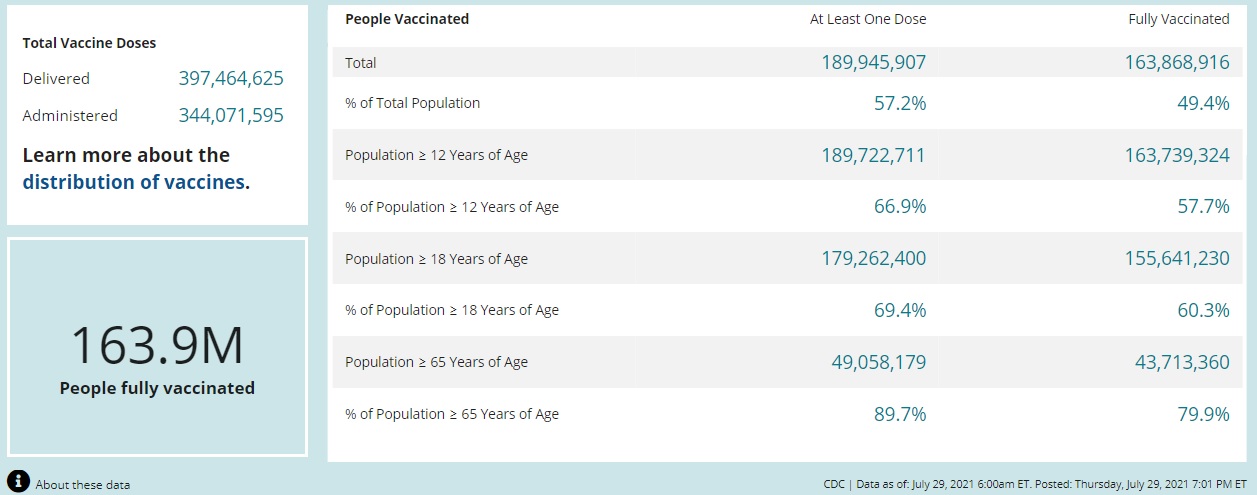

Most experts seem to coalesce around a herd immunity figure of between 80 and 90 percent for SARS-2. At present the U.S. stands at just under 50 percent vaccinated, leaving plenty of pockets of susceptible ground for the virus to cover yet. No matter how you tilt the picture, there’s a great deal of Covid-related hardship still ahead of us.

Breakthrough Cases

Let’s talk about breakthrough cases for a moment, as they’re understandably a central concern for those of us who took the social contract seriously and opted for the vaccine as soon as it arrived. Since no vaccine is 100 percent effective, some number of vaccinated people will go on to test positive for the virus. These are called breakthrough infections: the virus breaks through our wall of immunity, despite the boosted defense from the vaccine, and starts churning out copies of itself.

While breakthrough cases aren’t unexpected, even with the best vaccines, we do seem to be seeing more of them in the Delta-dominated stage of the pandemic. Notably, just how many we’re dealing with on a national level is difficult to pin down now that the CDC only tracks “severe” breakthrough cases — i.e. those ending in hospitalization or death — a controversial decision in place since the start of May. Even so, based on the existing body of evidence showing that Delta is better at evading immunity compared to earlier variants, it stands to reason that we should expect to see more of these cases as Delta further cements itself on the national map.

It’s important to emphasize at the outset that breakthrough cases by themselves should not be interpreted as a failure of the vaccines. “The success of the vaccine,” as Dr. Fauci reminded us recently, “is based on the prevention of illness.” Epidemiologists will tell you that infection is the hardest to prevent, followed by transmission, followed by symptomatic disease, followed by hospitalization and death. Any vaccine worth its salt will protect you from the last two, but may not shield you from the virus completely. Thus, a vaccine that turns an otherwise symptomatic case into an asymptomatic one still did its job. What we really want to know, then, is the most likely course of a breakthrough infection. If you, as a fully vaccinated person, are exposed to the Delta variant, what are the most probable outcomes? How worried should you be?

Let’s take each in turn. In terms of preventing infection altogether, efficacy varies depending on which vaccine and population are being studied, but it’s clear that none of the leading vaccines guard quite as well against Delta compared to Alpha. The unique mutations that gave rise to Delta enable easier access to our cells, as we might expect in response to the vaccine threat. Next, while Delta’s higher viral load already suggested an elevated risk of forward transmission, until this week we weren’t sure whether this applied only to unvaccinated people. As Apoorva Mandavilli reports in the NYT, fully vaccinated individuals “may be just contagious as unvaccinated people, even if they have no symptoms.” (This appears to be the key piece of evidence behind the CDC’s recently updated mask guidance.) Regarding symptomatic disease, here, too, the evidence indicates the vaccines perform slightly less well against Delta than Alpha, though not enough to raise alarm.

One point all the research agrees on, however, is that the Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines — the three shots authorized in the U.S. — are resoundingly effective at preventing serious illness and death, even with Delta around. We can be confident in this because as breakthrough cases have increased, we’ve not seen an associated increase in hospitalization or deaths. In Israel, for example, which has the highest density of vaccinated people anywhere in the world, serious Covid-related illness and deaths have continued to fall even as case numbers have risen. Israel’s Ministry of Health announced recently that Pfizer’s vaccine demonstrated 93 percent effectiveness at preventing serious illness and hospitalization. Similarly, national-level data from the UK shows that large spikes in cases have been met with only marginal increases in hospitalizations.

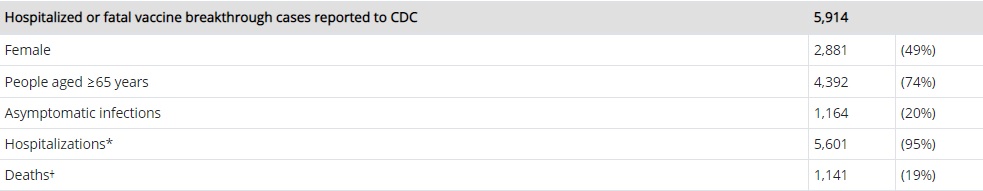

This is powerfully borne out by the CDC’s latest breakthrough data as well. Of the 161 million-plus vaccinations administered through July 19, 2021, 5,914 severe breakthrough cases have been reported, including 5,601 hospitalizations and 1,141 deaths. That’s already vanishingly low, but there are asterisks around all these numbers. First, three-quarters of the total cases involved people 65 or older, unsurprising given the fact that older adults are more susceptible to severe illness, irrespective of their vaccination status. Second, 1,821 of the cases involving hospitalization and death were asymptomatic or not related to Covid-19 at all. While these cases are included in the data sweep, they cannot necessarily be tied to Delta. Put differently, a positive test result does not mean cause of death. So what we’re really left with are 4,093 cases in which vaccinated people suffered a serious enough bout of Covid-19 that it landed them in the hospital or killed them. Such a low probability would be heralded as a triumph in the context of any other vaccine.

While it’s probable that breakthrough infections are undercounted at the moment, the available data speaks strongly to the success of the vaccines. The overwhelming majority of breakthrough cases have been mild or asymptomatic, and only in the rarest of rare cases has the infection progressed to something more serious.

[Update: As the CDC has restricted their breakthrough data in recent weeks to serious cases or those that create a burden on our health care system, other analysts have tasked themselves with casting a wider net. The first out of the gate is NBC News, and the results are encouraging. So encouraging, in fact, that it ought to change the way we talk about the topic entirely. Their analysis found a total of 125,682 breakthrough cases out of the 164.2 million people vaccinated since January. That translates to a rate of just under .08 percent, or less than eight-hundredths of a percent. The analysis compiled data from 38 states, with the remainder either not tracking breakthrough cases at all or disclosing only partial data. Even if we assume, though, that breakthroughs were undercounted by half, we’re still talking about fifteen-hundredths of a percent, or 1 in 650 people.1

To concentrate on a slightly raised concern of breakthrough cases is to place an unreasonable expectation on the vaccines and to take too dim a view of their unparalleled success. These are medical interventions designed in a matter of days in January 2020 that are effectively being deployed against a virus that has since evolved several times over. Mass coverage of what amounts to a tiny fragment of the overall population could further entrench vaccine hesitancy by focusing the spotlight on the wrong people. It’s not the vaccinated, who are three times less likely to be infected and 25 times less likely to die from Covid-19, but the unvaccinated who are chiefly responsible for transmitting the virus and prolonging the pandemic. We should continue to track breakthrough infections. But we should also be wary of straying too far off message at a time when trust in science and vaccines is at an all-time low.]

The throughline here, if you take nothing else away, is that getting vaccinated is the best way to protect yourself and others. That hasn’t changed. A vaccinated person is less likely to be infected in the first place, less likely to suffer from mild Covid, and even less likely to be admitted to the hospital or end up in a morgue. It’s the difference between having a gun-toting trespasser who means you harm on your mostly unprotected property versus a property laden with security alarms, concealed bear traps, land mines, and other active defenses. Sure, they might still make it through, but chances are the attacker will be turned away or disabled long before they can inflict real harm.

Waning Immunity?

The last item I want to cover is the possibility of waning immunity, a topic of much discussion in recent days. The length of protection afforded by the vaccines is still an open question — they simply haven’t been around long enough for us to draw any firm conclusions. It’s also a critically important one, because it could dictate our public health response, such as whether boosters are needed, or even entirely new vaccines.

Some answers are starting to trickle in from various countries, most notably a study released by Israel’s Health Ministry. Their latest data show a large and worrying drop in efficacy against both asymptomatic and symptomatic infections in recent weeks. As most of the country is vaccinated, about half of these cases were breakthrough infections. What’s most concerning are the time periods they looked at. From January to early April, when Alpha held a commanding lead, efficacy was estimated at 95 percent. From late June to early July, when Delta moved out in front, that figure plummeted to 39 percent. Protection against serious illness stayed at over 90 percent across both periods. Breakthrough cases, meanwhile, were more prominent among those vaccinated earlier in the year. The implication is that protection has tapered off since January, suggesting a shorter immunity period than we might have hoped.

There are many reasons to approach the Health Ministry’s latest study with some skepticism, however, reasons Israeli scientists raise themselves. It relies on a small sample, it measures only a tiny window of time, the age groups vary significantly across the two periods, and it’s highly inconsistent with data from other countries where Delta is also prevalent, including studies from the UK, Scotland, and Canada, which all derived efficacy ratings of 80 percent or higher.

Though the data is murky and will take time to sort out, it’s worth looking at the possibility the Israeli study is telling us something important about vaccine duration or potency. What might the future hold if their results amount to more than a statistical artifact? I see two plausible scenarios, one where new variants evolve to the point that they render our vaccines ineffective, and one where our immunity, whether vaccine- or infection-induced, wanes after a set period of time.

In the first scenario, Covid-19 would basically end up like the flu, requiring periodic shots to prevent infection from the active strain. These would need to be constantly updated to better match the genetic profile of newly circulating forms of the virus. How often we’d need them would depend on the rate of evolution of the virus, which could vary based on a number of factors, including the level of population immunity the virus encounters. Ideally, though, it would be less frequent than the flu vaccine, since coronaviruses generally mutate at a slower rate than the family of viruses behind influenza.

Under the second scenario, the vaccines themselves don’t change but their frequency does. Instead of offering indefinite protection, they may last up to six months, or two years, at which time you’d schedule a booster to top off your immunity. This would not be dissimilar to the vaccines for bacterial diseases like typhoid, tetanus, diphtheria, and meningitis, where immunity fades after a number of years. Given what we know about natural immunity from common cold coronaviruses, however, it’s unlikely that any Covid-19 vaccine will be able to match the ten-year duration conferred by tetanus and diphtheria shots, much less the lifelong immunity provided by measles and yellow fever inoculations. Nonetheless, the hope would be for vaccine-based immunity to extend longer than one year for most cohorts. Perhaps older age groups, and those with weaker immune systems, would need a booster once a year, while the rest of us could get by with a period of two years or more.

Finally, it should be noted that in the event of waning immunity, new cases would not constitute breakthrough infections. I think scientists and public health experts need to start underscoring now the important distinction between vaccine efficacy on the one hand and waning immunity on the other. If someone vaccinated back in May contracts Covid sometime next year, it doesn’t necessarily mean the vaccine didn’t take or that SARS-2 has outwitted their antibody arsenal. It may simply mean their immunity level has subsided, as happens with many vaccines, and it’s time to re-up.

Mask Up, Get Your Vaccine

All told, the risk calculus hasn’t materially changed from where we were in March of last year. Even if you aren’t personally at risk of serious illness from Covid-19, it’s more about those around you, who may be more vulnerable than you are. Asymptomatic transmission is now a universal concern, even if you’re vaccinated. It’s not just the vaccine hesitant folks you ought to be concerned about either, but the immunocompromised (at least 5 million), for whom vaccines may be less effective, children under 12 (50 million), who are not yet eligible to receive the shot, and the elderly, who may experience sharper drop-offs in vaccine protection due to their less resilient immune systems. Delta only raises the stakes for all of the above.

For these reasons, masking remains a favorable social safeguard whether you’re vaccinated or not, especially while in indoor, crowded spaces. That’s why it’s good to see the CDC recently changed its tune and now recommends masks for vaccinated people under certain conditions, particularly in areas with high case loads. This brings U.S. guidance more in line with the WHO’s in this regard, which has also called for the fully vaccinated to keep wearing masks in light of Delta.

And please, if you have yet to get your vaccine, do so. It’s the surest path out of this storm, and it can only happen once a critical mass of the country gets on board. No reasonable excuse exists for putting yourself and those around you at such inflated risk, especially once you consider how many people around the world lack access to a proven solution that you are — against all evidence — continuing to take for granted.

As we’ve come to expect from sifting through the science for the last year and a half, Delta’s impact is a developing story. The pandemic is still very much in flux, and evolution surely has more surprises in store for us yet. No public health guidance is set in stone, and we should be ready to adapt to whatever new conditions the variants and immunity thresholds throw at us.

Further reading:

- How the Delta variant achieves its ultrafast spread (preprint)

- How Worried Should Vaccinated People Be About the Delta Variant?

- What breakthrough infections mean for the Covid vaccines

- Rarely, Covid vaccine breakthrough infections can be severe. Who’s at risk?

- The Delta Variant Is Surging in Missouri

- Pfizer vaccine protection takes a hit as Delta variant spreads, Israeli government says

- Is Israel or the UK right when it comes to COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness?

- Nearly all COVID deaths in US are now among unvaccinated

- How Often Do the Vaccinated Spread Covid-19?

- American Dysfunction Is the Biggest Barrier to Fighting Covid

- Why You Should Still Wear a Mask—Even After Getting Vaccinated

- What Do We Know About the New Variant of Coronavirus?

- Why the Delta Covid Variant Is Making Herd Immunity Harder to Reach

- In Massachusetts, where the shoddily reported Provincetown outbreak took place, the Department of Public Health just released more granular data that makes the case for vaccines even stronger. Of all the breakthrough cases observed in Massachusetts to date, hospitalizations represented 0.009 percent of the total, while deaths made up just 0.002 percent. Of those hospitalized, 57 percent had underlying conditions. Among those who died, the median age was 82.5 years old, with nearly three-quarters having underlying conditions. That these numbers keep getting tinier the more we drill into them is a testament both to how effective these vaccines are at preventing severe Covid-19 and the unprecedented global effort to understand this disease and the virus that causes it. [↩]

Comments