More Climate Horrors for Bangladesh

The impacts of climate change fall disproportionately on vulnerable communities. We hear this repeated like a mantra, but it is simply an unfortunate fact that undeveloped nations have the least amount of resources to cope with a rapidly changing environment. In contrast with the Netherlands, thirty percent of which is below sea level and which has completely redesigned their cities in response, less moneyed nations lack the necessary capital to implement such comprehensive infrastructural overhauls. Even in the States, places like Newtok, Alaska and Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana are hopeless without bursts of federal assistance for mitigation, restoration or resettlement.

One of the more calamitous places to live in terms of vulnerability to climate is Bangladesh. Its three main threats include flooding, drought, and salinity. With its 700 rivers and thousands of miles of inland waterways, Bangladesh is uniquely susceptible to flash flooding during the rainy season. According to their government’s 2009 Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan, on any given year “approximately one quarter of the country is inundated.” And every four to five years, “there is a severe flood that may cover over 60% of the country and cause loss of life and substantial damage to infrastructure, housing, agriculture and livelihoods.” Even in Bangladesh, the report goes on to note, “it is the poorest and most vulnerable who suffer most because their houses are often in more exposed locations.”

The widespread erosion and flooding created by overflowing rivers is bad enough, but pales in comparison to the longer-term and more permanent threat of rising seas. Bangladesh is situated within the deltaic region formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers, and more than half of the country lies fewer than 5 meters (16 ft) above sea level. The gradually encroaching seas are forcing many communities — some of which have existed in their current state for centuries — to migrate inland.

The number of these so-called environmental migrants is expected to swell in the coming decades. Just three feet of sea level rise would plunge about 20 percent of Bangladesh underwater and potentially displace 30 million people. If the region sees five or six feet of sea level rise by the end of this century, a real possibility per the latest IPCC report, we’re talking about upwards of 50 million migrants.

While it may seem counterintuitive in a country surrounded by so much water, Bangladeshis also have to contend with periodic drought. This is mostly a function of the region’s climate profile, in which it receives too much moisture in monsoon season and too little during the dry months. Those most affected tend to live in the northwestern districts, as these areas typically receive less annual rainfall relative to other parts of the country. A prolonged shortage in rainfall can devastate local agriculture and ecosystems in the form of reduced crop growth and yield and the loss of livestock.

A more esoteric cause of Bangladesh’s water shortage woes that bears mentioning stems from its water-sharing agreements with bordering nations. Over fifty of the rivers flowing through Bangladesh territory are considered what are called trans-boundary rivers, the resources from which are shared with India and Myanmar. Both of these countries withdraw water upstream with the help of large-scale water management facilities, disrupting the river’s natural flow. Not only does this result in lower yields for Bangladesh during the dry season, but it also impacts groundwater recharge leading to an overall moisture loss in the northwest part of the state. The details of these agreements are politically complex, but it seems clear that Bangladesh is getting the short end of the stick here due to the climatic knife-edge on which much of the country exists.

Perhaps the most serious threat posed by droughts, however, is access to fresh drinking water. Currently, about 1.7 billion people — or one-quarter of the world’s population — live in countries that are water-stressed. Drought conditions such as those plaguing northwestern Bangladesh make potable water scarce and facilitate the spread of disease like malaria due to the stagnant pools of water left behind from the rainy season.

The logic is inescapable that a monotonically warming planet intensifies the conditions for millions of people living in Bangladesh. Climate change causes sea levels to rise, reducing the area of habitable land available to vulnerable communities. Climate change increases the amount of moisture in the air, accelerating the hydrological cycle, thereby leading to more (and more intense) precipitation events. At the same time, rising temperatures decrease the amount of moisture stored in soils. These and other readily observed trends exacerbate conditions in places prone to nuisance flooding and persistent drought like Bangladesh.

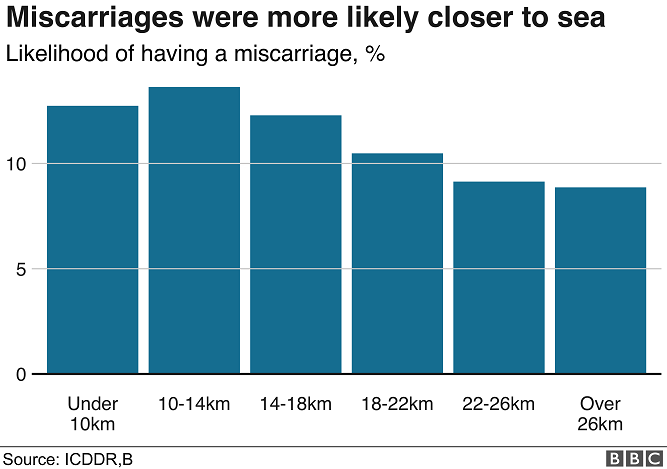

As if all of the above weren’t cause enough for alarm, the salinity of freshwater streams used by sea-proximate communities is increasing, which is now reportedly contributing to the higher incidence of miscarriages in the region. As the BBC writes, “When sea levels rise, salty sea water flows into fresh water rivers and streams, and eventually into the soil. Most significantly, it also flows into underground water stores – called aquifers – where it mixes with, and contaminates, the fresh water. It is from this underground water that villages source their water, via tube wells.”

Families living in the coastal zones are consuming three times more salt each day than inland families, and scientists believe this is having a measurable effect on miscarriage rates throughout the country. Apart from complicating pregnancies, excess salt intake also increases the risk of strokes and heart attacks and can cause hypertension in adults. We can expect to see more people suffering from these infirmities as more and more salt makes its way into freshwater basins.

In light of these developing horrors, what will we tell our kids and our grandkids when they ask why more wasn’t done to respond to the manifold risks brought on by climate change? What will we say to them when they ask us why we didn’t listen to the scientists? We told ourselves it didn’t matter.

As Trent Reznor intones in his song Zero Sum, “May God have mercy on our dirty little hearts.”

Further reading:

- How climate change could be causing miscarriages in Bangladesh

- Climate Change Impacts in Bangladesh

- The Unfolding Tragedy of Climate Change in Bangladesh

Feature image credit: DfID/Rafiqur Rahman Raqu

Comments