How Much of America Actually Believes in Climate Change?

What percentage of Americans agree with the science of climate change? It’s a trickier question than you might think.

As a topic of rigorous study for decades, you’d think we’d have a relatively straightforward answer. We know from a 2014 report, for example, that the US is the single largest haven for climate denial when put up against every other country surveyed, including Russia. We also know, thanks to painstaking work by a number of dedicated teams, what Americans think on this issue down to the county level. Upon closer inspection, however, several factors emerge to complicate the pursuit of a uniform tally.

What you’ll notice right off the bat when canvassing the available data is how discrepant the figures can be from group to group. This is due in part to differences in methodology of course, but especially to how the questions in a survey are phrased. As has long been understood, even slight variations in the wording of a question can materially affect the results of a given poll.

Consider the following five statements:

- The climate change we are currently seeing is largely the result of human activity. (Source)

- Climate change is caused entirely or mostly by human activities. (Source)

- Global warming is caused mostly by human activities. (Source)

- Almost all climate scientists agree that human behavior is mostly responsible for climate change. (Source)

- Human action has been at least partly causing global warming. (Source)

Would it surprise you to learn that outcomes differed, in some cases dramatically as we’ll see in a moment, for each of the above statements? When creating an opinion poll, word choice matters. Notice how some of the pollsters chose to use ‘climate change’ (less specific), while others opted for ‘global warming’ (more specific). These terms are not equivalent, and the decision to use one over the other most certainly will impact the results. I also count at least five adverbs above, each carrying its own set of connotations to a reader. Variation in terminology and phrasing is perhaps the single biggest reason for the discernible spread across different polling groups and why direct comparisons should be avoided.

Before we dive into some of the more recent polling data, we first need to identify which question we actually want the answer to. Do we wish to know how many people concur with the science, or how many dispute it? It’s not a simple matter of finding one of these percentages and then substracting it from 100 to get to the other, either, since most polls carve out a space for the undecideds by including selections like “I don’t know” or “Not sure.” Some respondents may also leave some questions blank.

Let’s assume we want to know the portion of the public that concurs with the science. Here an important distinction arises: by “the science,” do we mean (1) the climate is changing, or (2) the climate is changing due to human activity. Many surveys break these out separately. As we might expect, more people have historically co-signed (1) than (2), clinging to the bunkum that any observed change is part of natural climate variability. It could be argued that (2) is the one that matters because it speaks to the question of scientific consensus. Sure, rejecting either statement makes one a climate ‘denialist‘, but only those who affirm both are in agreement with the plurality of scientists in the field. Getting (1) right and (2) wrong is akin to earning partial credit on an exam, in the same way as saying organisms change over time while rejecting the evolutionary mechanism of Darwinian selection.

Furthermore, those who fall into this camp are generally no more keen on altering their behaviors or advocating that others do the same, or championing effective climate policy, such as scaling back on fossil fuel burning — an irrefragably human endeavor — in favor of renewables than those who reject both statements. They’re just as likely to have swallowed and to pass on the same misinformation and suspect sources, and therefore just as motivated to brick popular discourse on the topic and hinder the path to a sustainable future. For these reasons, when people ask, ‘what percentage of Americans accept climate change,’ what we’re really — or should be — after is (2). Keep this distinction top of mind as we delve into the polling.

On to the Data

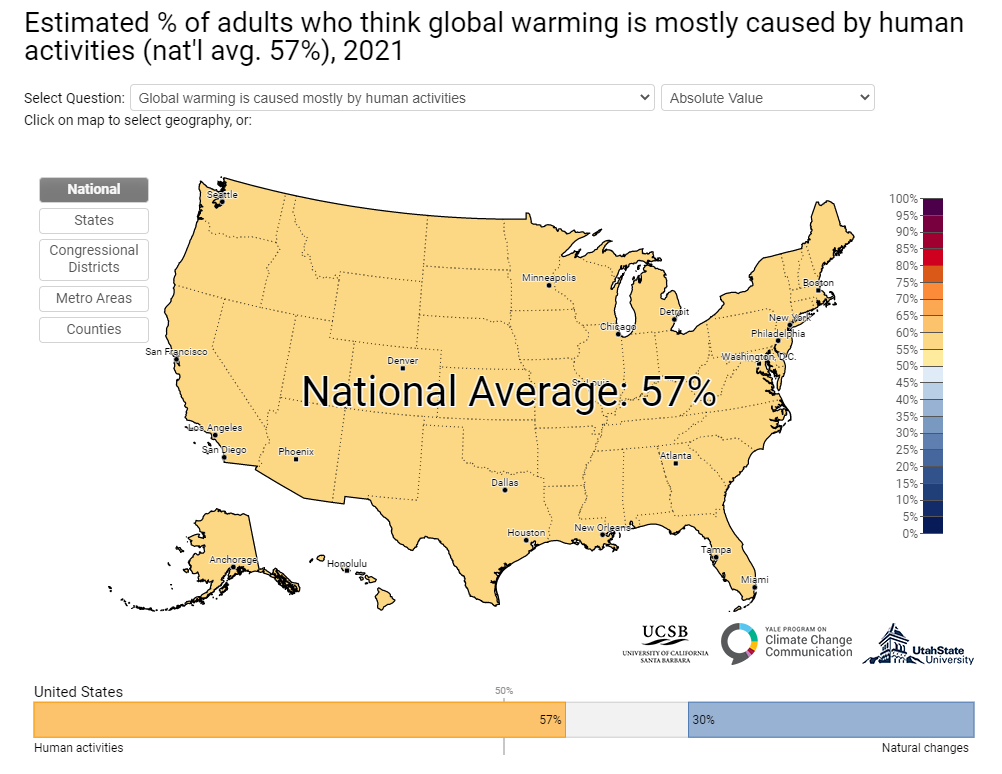

There are several groups doing this work, but at the top of the list is the Climate Change Communication team at Yale, whose mission is to tackle the gap between what scientists and the public know. You can always find their latest opinion maps here, where they break down US sentiment in terms of Beliefs, Risk Perceptions, Policy Support, and Behaviors all the way down to the county level. According to their most recent survey data from fall 2021 (just posted last week!), they found that 72% of US adults think “global warming is happening,” while 57% think “global warming is mostly caused by human activities.” Their data also show that only 14% of US adults outright answer “No” to the question of whether global warming is happening at all, while 30% think it is but that the change is natural.

To see how these numbers have changed, the Yale team conducted the same poll five years earlier. For 2016, the equivalent figures are 53% who agreed that global warming is caused mostly by human activities and 70% who agreed that global warming is happening without regard for cause. So we’ve seen some incremental progress in that time. To get a glimpse of just how dramatically the numbers can vary based on linguistic choices, a poll conducted by Pew that same year found that just 27% of US adults accept the scientific consensus, concurring with the statement that “almost all scientists agree that human behavior is mostly responsible for climate change.” That’s a remarkable discrepancy between Yale and Pew, but one that’s no doubt best explained by the discrepant language: “almost all” is more binding than “mostly,” and, absent other relevant information known by the participant, likely to net fewer endorsements. Again, wording matters.

Next let’s turn to two surveys given mere days apart in November 2018 that arrived at wildly different outcomes. Monmouth University published a poll that year which found that 78% of Americans agree “that the world’s climate is undergoing a change that is causing more extreme weather patterns and the rise of sea levels” (up from 70% in their Dec. 2015 poll), but that only 29% agree that the change is “caused more by human activity” than “by natural changes in the environment, or by both equally” (compared to 27% in their Dec. 2015 poll). This result is more in line with Pew’s data from two years earlier. A 2018 survey from the University of Chicago, however, found that 71% (7 in 10 Americans) “think climate change is happening” and 60% (6 in 10) “think climate change is caused entirely or mostly by human activities.” That’s more than double Monmouth’s number, illustrating the extent to which study design can touch the final result.

At the top end of the spectrum, a Resources for the Future survey from August 2020 found that 82% of Americans “believe human action has been at least partly causing global warming.” Compared to the rest of the polling data I have in front of me and even after accounting for sampling error, RFF’s results paint the rosiest picture of US public opinion to date, coming in 22 percentage points higher than University of Chicago’s 2018 poll and a full 25 points higher than Yale’s latest poll. Here again, we probably have RFF’s more relaxed phrasing to thank for that.

To sum up, there’s no clear-cut answer to how many Americans accept or deny climate change, as so much depends on how you word the question and the methodological decisions made at the outset. Based on survey and polling results dating back to the Paris accord, the portion of America that considers recent warming anthropogenic in origin — my barometer of choice for gauging climate literacy — ranges anywhere from 27% to 82%. That’s an absolutely massive gap, a reflection of the unique language and design choices used in each poll. As we’ve seen, mild alterations in syntax can completely rewrite the national map.

But since “it depends” is an unsatisfying answer, I recommend the following approach. Instead of fruitless attempts to homogenize results from different polls to come up with a ‘true’ figure, track the trendline of a single group that’s been gathering reliable data for a while, such as the climate comms team at Yale. Based on their data, public acceptance of human-caused climate change has ticked slowly upward over the last decade or so, with slightly fewer than 6 in 10 (57%) Americans currently answering the question correctly. Yale’s numbers are usually the ones I cite because I trust their methodology and because I see respected experts in the field regularly citing their work. Theirs is as solid a dataset as you’re likely to find, and offers regional granularity to boot.

Feature image credit: Getty Images

Comments