‘American Heretics’ Film Offers a Hopeful Vision for Religion’s Future

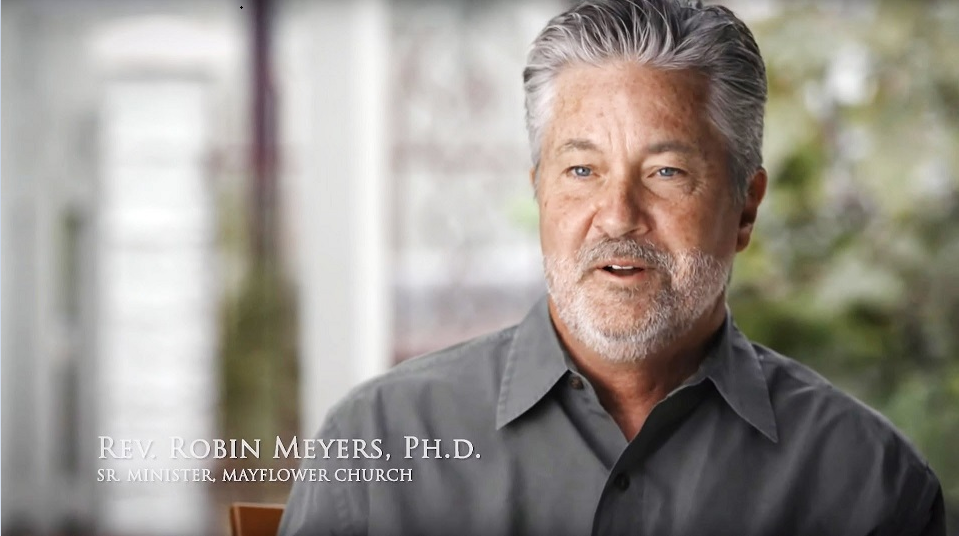

“The interesting thing about people who say they’re certain,” observes Pastor Robin Meyers of Mayflower Congregational, “…then you need no faith.”

A documentary project that debuted in the summer of 2019 can now be viewed on YouTube in its entirety. Beautifully titled American Heretics: The Politics of the Gospel, the film is made available courtesy of Secular Student Alliance. The first hour and a half is the documentary, while the remaining runtime features a Q&A with one of the pastors, Reverend Marlin Lavanhar. The film profiles two different church communities in Oklahoma, one mainline Christian, the other Unitarian, each helmed by pioneering idealists devoted to reclaiming faith from the clutches of right-wing contemporary evangelicalism. It’s a timely and personal glimpse into the hardscrabble realities of establishing a more tolerant church presence in rural America.

Oklahoma is often considered the “reddest” state in America. Every single county went to Trump in 2016. Naturally, it also happens to be the veritable epicenter of the Bible Belt, with Tulsa occasionally designated the “buckle.” Roughly 79% of Oklahomans identify as Christian, predominantly Southern Baptist. The idea of liberal, justice-oriented churches thriving in such an unwelcoming, if not outright hostile, environment would strike many as preposterous on its face. And yet, as the film shows, that’s just what’s happening thanks to a few blessedly dedicated iconoclasts willing to challenge the statewide hegemony of the Christian right.

The Mayflower Congregational United Church of Christ in Oklahoma City and All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa, as havens for free thought and social-conscious messaging, provide a clear contrast to the thousands of Trumpified churches dotting the countryside. Comfortable with doubt and uncertainty, these are places that speak to rational believers who wish to be part of a community that espouses a Christianity decidedly less embarrassing to empathetic adults capable of critical thought. Pastors like Robin Meyers of Mayflower articulate approaches to faith and the Bible that don’t line up with those of Franklin Graham, Jerry Falwell Jr., Mark Driscoll, Paula White, Robert Jeffress, Joel Osteen, and other evangelical heavyweights.

Central to the fissiparous nature of contemporary Christianity is hermeneutics — or the overall lens through which one views the Bible. The question of inerrancy is the elephant in the room that more often than not bogs down our theological disagreements, and though it’s never mentioned by name in the film, many of the issues explored run right into it. Debates over immigration and foreign policy, same-sex marriage, whether women can occupy leadership roles in the church, wealth and racial inequality, even climate change, all turn on the differing interpretive choices of one Christian tradition or another.

It’s a point of separation that’s highlighted especially well in the film thanks to the inclusion of New Testament scholar Dr. Bernard Brandon Scott. His didactic monologues help drive home that, at bottom, there’s a difference between how evangelical fundamentalists approach the Bible and how mainline Christians approach the Bible, and that difference matters. To be sure, biblical interpretation is a quandary that’s been with the church from the fourth century onward and, indeed, is responsible for much of the major denominational branching observed since that time. But the role of the Bible in relation to Christian identity, and the amount of deference due the texts in resolving the issues of our time, is the gravamen underlying much of the internecine Christian culture war today.

The cardinal theological and intellectual error committed by fundamentalists — apart from their ideological rigidity, perhaps — is their indifference to historical context. A collection of texts divorced from its original setting and intent sets up the expectation that the Bible can speak to whatever modern concerns one wishes to bring to it. Mainline Christians, by contrast, largely understand that a more responsible way to engage the Bible is not with a literal or scientific reading, but rather with one that seeks to understand these writings in light of their ancient context and the perspectives and concerns of its (eminently fallible) composers. The latter outlook allows the mainline Christian to dispense with the notion that the Bible must inform every aspect of modern social, political, and theological life.

Put another way, mainline Christians believe God is larger than the Bible, even while the Bible points to God, while fundamentalists in large part believe God and the Bible to be one and the same. For the evangelical fundamentalist, thus, the Bible is, in effect, an idol. By equating the Bible with God itself, they elevate a physical text to an object of mystical devotion. As Dr. Scott pointedly remarks early on, the kind of idolatrous attachment that treats the Bible as essential to Christianity is an awkward position to stake out since in fact there was no biblical canon until some three centuries following Jesus’ death.

Such a paradigm extends beyond mere theology and into culture, as we’ve witnessed in recent decades, most poignantly over the last four years. The unholy alliance between Trump and evangelicals — and white evangelicals in particular — is a topic that’s been probed at length by folks much smarter than me, but there does seem to be some connective tissue between regarding the Bible as a supreme and inerrant authority on the one hand, and the willingness to not only embrace a coarse strongman like Trump but to overlook his obvious lies and contradictions and insist he can do no wrong in the face of incontrovertible evidence on the other. Amid repeated setbacks in the arena of politics and social mores, evangelicals see in Trump a return to form, a chance to recover the patriarchal, white nationalist paradigm under which they’ve always flourished.

But if the Trump era has taught us anything about religion, it’s that one can no longer compartmentalize their faith from their politics. Self-aware Christians have awoken to the fact that siding with a president who dehumanizes asylum-seeking refugees by separating their families and stuffing them in overcrowded facilities is a monstrous affront to the gospel; that demonizing outsiders and ethnic minorities (categories to which, as a Jew living under Roman rule, Jesus belonged) cannot be reconciled with the texts of the New Testament; that abject cruelty for cruelty’s sake is incongruous with the lovingkindness exemplified in the figure of Jesus. Such Christians exist everywhere in America, including in Oklahoma.

Toward the end of the film, Reverend Carlton Pearson, who once served under televangelist Oral Roberts, says that he believes churches like Mayflower and All Souls Unitarian will be the “premier megachurches in the next 10 years.” I don’t know how his prediction will pan out, but I do think that something has to give in terms of the relationship between evangelicalism and Trumpian politics. For Christianity to remain relevant in a rapidly secularizing society, it must examine its theology in response to new evidence and information and to the forces of social change. It cannot continue clinging to discredited ideas, outmoded belief systems, and archaic cultural conventions while expecting to appeal to informed, rationally minded people in the twenty-first century — not if they want to stop seeing younger people, who tend to have much lower tolerance for bigotry and Trumpist behavior, disaffiliate.

To be sure, the roots of this culture will be difficult to extirpate. Fundamentalist churches have been committing open intellectual fraud on their congregations for decades now, adopting a kind of absolutism to ward off disagreement and branding anyone who disagrees with them as ‘heretics,’ atheists, and the like. As a result, their fervent members are none too disposed to step out of their echo chamber and honestly consider competing perspectives, conditioned as they are to rationalize away whatever dissonance happens to penetrate their carefully managed bubble. I hardly expect this social climate to deteriorate completely in the coming years, and I anticipate the voices that have fallen out of favor will incline toward more incendiary (and more infantile) rhetoric as the cultural battle lines continue to sharpen. But if these communities want to slow the hemorrhaging of young folks in particular, at a minimum they’ll need to shed their Trumpist associations.

As for whether a more mature and sensible evangelicalism will eventually displace what we see today across rural America, I’m admittedly less hopeful. I actually don’t think the regressive, reactionary strand of Christianity can be ‘saved’ from the dishonesty of the antiscience, anti-academia, anti-social justice industrial complex, because the patient could not possibly survive the surgery. The inhumility and incuriosity, to say nothing of the rampant hypocrisy, are too deeply baked into the cultural psyche. My hope, though, is that while evangelical churches may continue to exist, with all their backward ideological baggage intact, we’ll see them become smaller in size and shallower in influence as their more cognizant counterparts leave the fold for more mainline, progressive-postured churches.

Further reading and resources:

- Secular Student Alliance premiere of “American Heretics: The Politics of the Gospel”

- Defending God, No Matter the Cost

- Creating a More Inclusive Christianity Takes More than Love Alone

- Review: The Unlikely Disciple

- Review: God Behaving Badly

- Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation

Comments