The End of Prison

“Put simply, this is the era of the prison industrial complex. The prison has become a black hole into which the detritus of contemporary capitalism is deposited.”

I feel a mix of inspiration, remorse, and frustration to know that the conversation around mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex was happening in earnest at the turn of the century — as I was making my way through middle school. Inspiration because brilliant intellectuals like Angela Davis have challenged the status quo for decades now, beckoning us to reimagine our approach to state punishment as more of our fellow citizens begin a new life behind bars. Remorse because so much of this conversation is as new to me as it is utterly shocking. But mostly I feel frustration that after all these years, advocacy efforts continue to be thwarted by perverse incentives and structural inertia.

Angela Yvonne Davis is no stranger to the injustice of the American prison system, having served a 16-month stint in New York City in 1971, partly in solitary confinement. She was briefly placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list courtesy of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, at the time only the third woman to make the list. She was ultimately acquitted of all charges. Following her incarceration, Davis became an icon for the prison abolition movement, spearheading a number of causes and organizations, including Critical Resistance, a grassroots group dedicated to dismantling the global prison industrial complex. Her treatise, Are Prisons Obsolete?, shines a light on the catastrophe of mass incarceration, examining its origins and evolution, and points us toward a new vision of justice.

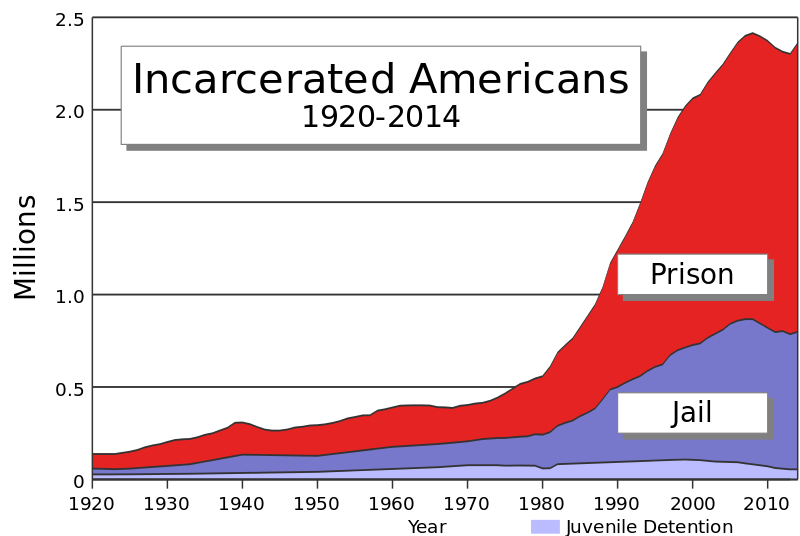

Regrettably, the problems she identifies have only grown more pressing in the wake of her bracing manifesto. Writing in 2003, Davis cites an incarcerated population of 2.1 million, while the latest figure from the Prison Policy Initiative stands at 2.3 million. To unpack this number a bit further, as of last count there are 2,270,800 people confined to 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails, not inclusive of those in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the US territories. If we expand the scope to all US adults under some form of correctional supervision, the number swells to 6.8 million. These figures can be contrasted, as Davis does, with the late 1960s, when the prison population stood at under 200,000.

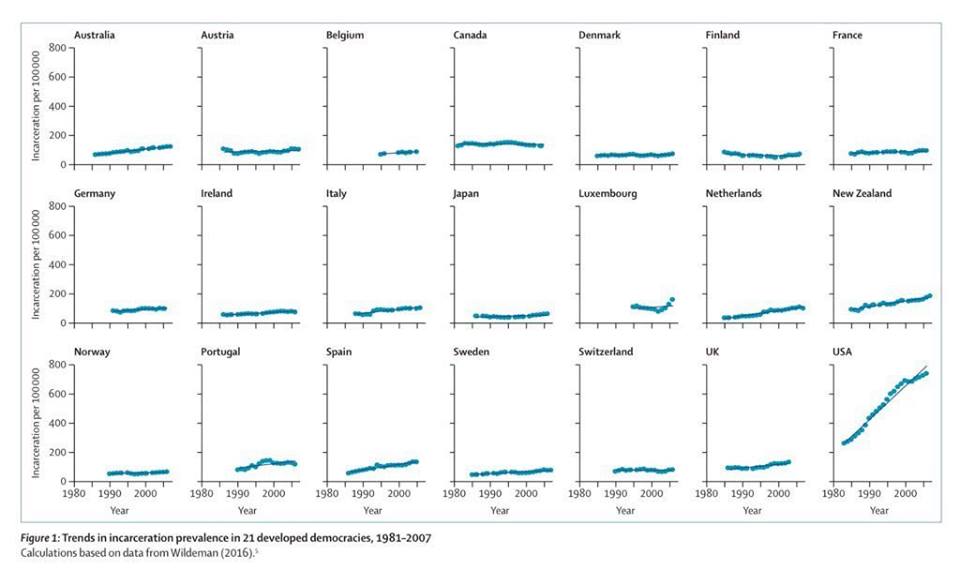

These are not typos. By any measure, the US has by far the largest prison population in the world and the highest per-capita incarceration rate in the world. In fact, despite making up about 5% of the world’s population, the US accounts for between one-fifth and one-quarter of its prisoners. According to data compiled by World Prison Brief and the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, the US rate is 655 per 100,000 people, versus 107 for Canada, 135 for England & Wales, 169 for Australia, 124 for Spain, 104 for Greece, 60 for Norway, 63 for Netherlands, 39 for Japan, and 37 for Iceland. No other country is within hailing distance when it comes to the number of citizens it locks up.

In her introduction, Davis reflects back on how dramatically, and how quickly, these numbers have grown since she took up the mantle of confronting one of the largest and most consistent state-sponsored social programs of our time:

“When I first became involved in antiprison activism during the late 1960s, I was astounded to learn that there were then close to two hundred thousand people in prison. Had anyone told me that in three decades ten times as many people would be locked away in cages, I would have been absolutely incredulous. I imagine that I would have responded something like this: ‘As racist and undemocratic as this country may be, I do not believe that the U.S. government will be able to lock up so many people without producing powerful public resistance. No, this will never happen, not unless this country plunges into fascism.'” (p. 11)

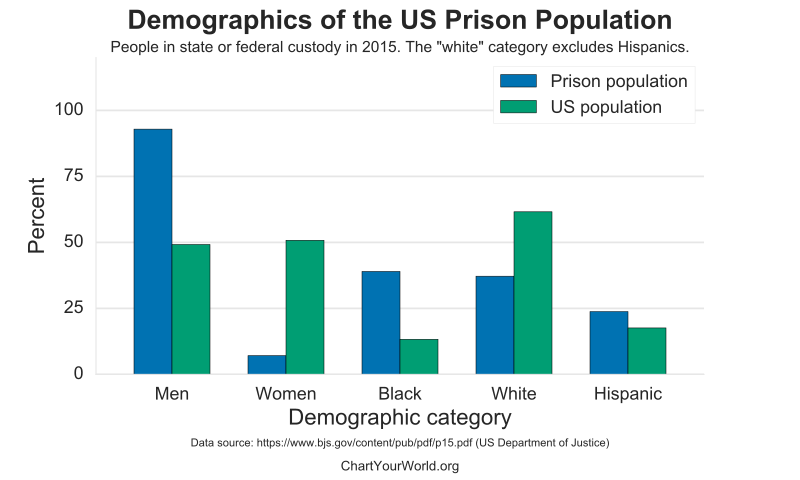

The situation becomes more troublesome when you parse the data from the perspective of race. Seventy percent of the US prison population today is composed of racial minorities, with Black women and Native Americans the fastest growing groups in this pie. As is also well known, the Black imprisonment rate is more than 5 times the white imprisonment rate, and the rate for African American women is more than twice that of white women. For 2018, 1,730 out of every 100,000 African Americans were behind bars, while the equivalent Hispanic and white per-capita rates were 856 and 274, respectively. Again, if you think those are typos, you haven’t been paying attention.

A different way of thinking about this is that although African Americans and Hispanics make up 32% of the US population, they comprise over half — 56% in 2015 — of all incarcerated people. If African Americans and Hispanics were incarcerated at the same rates as whites, prison and jail populations would decline by almost 40%. Tell me that wouldn’t save a hefty chunk of the more than $80 billion the US government spends on imprisonment every year.

Davis explains how the effects of mass incarceration have always fallen most heavily on African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinx communities:

“The racialization of crime…did not wither away as the country became increasingly removed from slavery. Proof that crimes continues to be imputed to color resides in the many evocations of ‘racial profiling’ in our time. That it is possible to be targeted by the police for no other reason than the color of one’s skin is not mere speculation. Police departments in major urban areas have admitted the existence of formal procedures designed to maximize the numbers of African Americans and Latinos arrested—even in the absence of probable cause.” (p. 31)

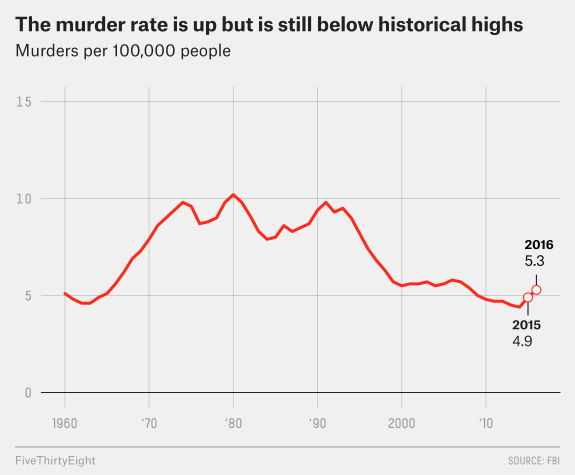

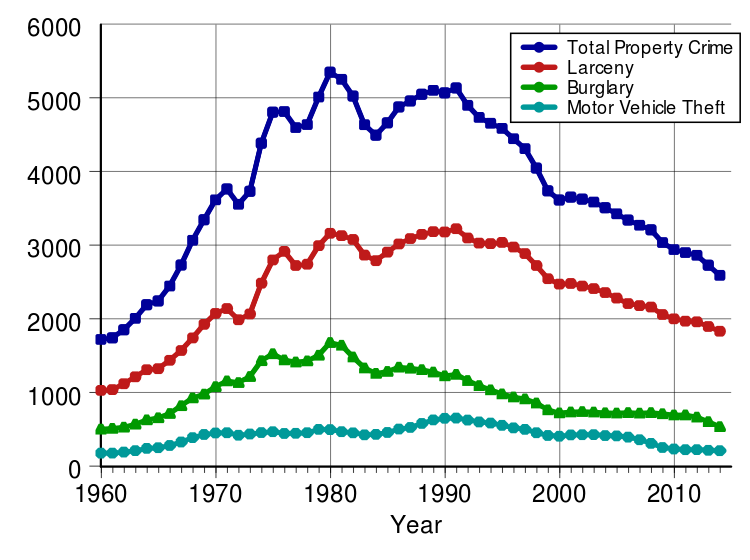

You might think that the era of incarceration in which we still live at least has logical or defensible origins. You might think, as I once did, that our heightened avidity for removing growing numbers of citizens from society and placing them behind bars was coincident with rising levels of crime. But in fact, during the Reagan-Bush years, when the “tough on crime” ethos took center stage and crime was hyped as among the greatest social ills of the day, crime statistics of all varieties, including homicides and property crimes, were in decline.

Both the murder and property crime rates peaked in 1980, and were already falling by the time Reagan took office. Though violent crime saw a brief resurgence in the late 1980s and early 90s, it fell sharply afterward and has continued to decline over the past quarter century. A very similar story played out for the property crime rate, which peaked in 1980, increased between Reagan’s second term and Bush Sr.’s first term, and has consistently declined thereafter. Yet inmate counts continue to climb.

What did happen, which has ended up accounting for much of the increase in the US prison population, was an expansion of criminalized behavior. As Davis notes, at the same time that prison construction took flight across the country, “draconian drug laws were being enacted, and ‘three-strikes’ provisions were on the agendas of many states.” Akin to how a broadening of diagnostic techniques accounts at least in part for the increase in cases of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in recent decades, new classifications of criminal conduct help explain the proliferation of imprisoned persons. This shift in focus manifested in harsher sentencing practices for petty drug offenses and disproportionate numbers of incarcerated Black and Brown Americans. Today, there are more people behind bars for drug offenses than all of the people who were in prison or jail for any crime in 1980.

As our prison population started spiraling, media coverage generated greater interest in crime-centric lawmakers and a consequent demand for more and larger prisons. Of course, the sorts of crimes that garner broad public interest are not the sorts of crimes for which increasing numbers of people were being sent to jail, but that didn’t stop local news from concentrating its attention on murders and shootings, which were falling throughout the 1990s. As journalist Vince Beiser reported in 2001, “According to the Center for Media and Public Affairs, crime coverage was the number-one topic on the nightly news over the past decade. From 1990 to 1998, homicide rates dropped by half nationwide, but homicide stories on the three major networks rose almost fourfold.” During this pivotal decade, when its influence could have helped move the needle in the opposite direction, mainstream media’s role in shaping public perceptions of crime instead abetted politicians and interest groups whose success was wedded to mass incarceration.

Our incarceration binge thus began with opportunistic politicians creating false narratives about public endangerment from criminal elements, which fostered waves of new legislation, including tougher sentencing laws that kept offenders locked up longer. An ongoing prison construction boom shortly followed, carving out niches for private industry in the form of lucrative government contracts. This unprecedented deployment of capital was matched by enormous social costs absorbed principally by communities of color for generations. Meanwhile, the misleading narratives coming from the top were zealously fed by the media, preying on the public’s fear of crime to boost ratings and thereby reinvigorating support for legislative crackdowns along with new bursts of spending on federal and state penitentiaries.

The Prison Industrial Complex

With or without hindsight, it should have been obvious that such a pernicious cycle — kept afloat by Republican and Democrat administrations alike — would culminate in what we refer to today as the prison industrial complex (PIC). Though our understanding of this phenomenon has evolved over time, Davis describes it as the sprawling web of relationships that exist between private entities and the prison institution, together with the incentive structures that sustain it. Despite the tangible associations the term tends to connote, it is not an isolated, physical entity but a far more sinister force that since its inception has served to exacerbate a number of existing social problems.

“Since the 1980s, the prison system has become increasingly ensconced in the economic, political and ideological life of the United States and the transnational trafficking in U.S. commodities, culture, and ideas. Thus, the prison industrial complex is much more than the sum of all the jails and prisons in this country. It is a set of symbiotic relationships among correctional communities, transnational corporations, media conglomerates, guards’ unions, and legislative and court agendas.” (p. 107)

Due to the tremendous demand for prison space that accompanies the war on crime, and the large variety of goods and services a skyrocketing prison population requires, corporate involvement in state punishment has escalated over the last four decades. From construction contracts and surveillance technologies to health care, food, and phones, private companies sell their products to correctional facilities in all fifty states, deepening the ties between punishment and profit. And as publicly managed facilities have become overcrowded, federal and state governments have increasingly turned to private companies to share in the housing burden.

“At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the numerous private prison companies operating in the United States own and operate facilities that hold 91,828 federal and state prisoners. Texas and Oklahoma can claim the largest number of people in private prisons…In arrangements reminiscent of the convict lease system [in the aftermath of the Civil War], federal, state, and county governments pay private companies a fee for each inmate, which means that private companies have a stake in retaining prisoners as long as possible, and in keeping their facilities filled.” (p. 95)

Though private prisons still make up a minority of total prisons in America, the trend toward for-profit prisons is an alarming one. Davis cites Joel Dyer in his book The Perpetual Prison Machine: How America Profits from Crime: “In 2000 there were twenty-six for-profit prison corporations in the United States that operated approximately 150 facilities in twenty-eight states.”

I wanted more recent data on this, so I did some desk research. Since 2000, the federal prison system alone has seen a 120% increase in the use of private prisons, with the number of people housed in private facilities growing 47% over this period. As of 2016, 128,063 people serve their time in for-profit prisons, or 8.5% of the total state and federal prison population. And now, with the previous Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ decision to overturn the Obama-era policy that sought to phase out private prison contracts, we can expect the growing corporatization of the prison economy to continue well into the future.

Women and Gendered Punishment

Davis also delves into the unique challenges women face in the prison, in what may be the most eye opening chapter of the book. It wasn’t until the 1870s, thanks to the decadeslong struggle of Quaker reformers, that separate prisons for women started to appear in the United States. But because the prison is an environment originally devised by and constructed for men, gender-specific accommodations have always been lacking, even in the twenty-first century.

There are now more than 111,000 women in prison nationwide, a large majority of whom have chronic histories of physical and substance abuse, HIV, hepatitis and other illnesses. The differing health care and other needs of women and men is a reality not often reflected at the institutional level. Private sector involvement in both women’s and men’s prisons, moreover, means that those signing the checks tend to cater to the lowest common denominator, without consideration of the needs or vulnerabilities of female inmates.

Integral to this history is how preconceptions about gender have informed the ways in which the state has punished women. Women historically have been given harsher sentences than men, which Davis owes to the markedly different attitudes society has about women convicts compared to their male counterparts. “Masculine criminality,” Davis writes, “has always been deemed more ‘normal’ than feminine criminality.” (p. 66) Therefore a woman committing the same crime as a man must be that much more socially deviant and criminal in nature, with fewer possibilities for reform and redemption.

“Male punishment was linked ideologically to penitence and reform. The very forfeiture of rights and liberties implied that with self-reflection, religious study, and work, male convicts could achieve redemption and could recover these rights and liberties. However, since women were not acknowledged as securely in possession of these rights, they were not eligible to participate in this process of redemption. According to dominant views, women convicts were irrevocably fallen women, with no possibility of salvation. If male criminals were considered to be public individuals who had simply violated the social contract, female criminals were seen as having transgressed fundamental moral principles of womanhood.” (pp. 69-70)

These sexist tropes went on to dictate the gendered punishment programs administered by the state. Unlike the rehabilitation efforts afforded men which focused on isolation and hard labor, programs for women centered more on promoting domestic skills. This was surely a reflection of the fact that not only did women have fewer rights than men, but they also had fewer options both in and outside the prison walls. Drawing from Joanne Belknap’s work, the aim of one of the first US reformatories opened in 1874 was to:

“…train the prisoners in the “important” female role of domesticity. Thus an important role of the reform movement in women’s prisons was to encourage and ingrain “appropriate” gender roles, such as vocational training in cooking, sewing and cleaning. To accommodate these goals, the reformatory cottages were usually designed with kitchens, living rooms, and even some nurseries for prisoners with infants.” (p. 71)

Those women that could not be “reformed” in the traditional sense would be passed off to the clinician and issued psychoactive substances as treatment. Here again, because of the perception that female crime was unorthodox and outside the bounds of normal female behavior, perpetrators were deemed to be of unsound mind. This meant that women, unlike men, were more likely to be treated clinically rather than criminally, with more women serving time in psychiatric institutions than in prisons. “That is,” Davis sums up, “deviant men have been constructed as criminal, while deviant women have been constructed as insane.” This paradigm runs through to present day, with imprisoned women far more likely than men to be given psychiatric drugs as part of their treatment plan.

Though modern conditions in women’s prisons are no doubt an improvement over historical times in terms of more humane treatment and the variety of services available, in many ways the system has failed to keep pace with the changes that the introduction of greater numbers of women requires. The widespread and well documented sexual abuse of imprisoned women presents an enduring crisis for which the state cannot relinquish responsibility. Routinization of practices like the strip search and body cavity search, often conducted by male officers, amounts to state-sanctioned sexual assault, as recounted by ex-incarcerated activists like Assata Shakur — now living in Cuba after being granted political asylum in 1984 — and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and illustrated in hit series like Orange is the New Black.

“As the level of repression in women’s prisons increases…sexual abuse…has become an institutionalized component of punishment behind prison walls. Although guard-on-prisoner sexual abuse is not sanctioned as such, the widespread leniency with which offending officers are treated suggests that for women, prison is a space in which the threat of sexualized violence that looms in the larger society is effectively sanctioned as a routine aspect of the landscape of punishment behind prison walls.” (pp. 77-78)

Abolition, Not Reform

Finally, Davis turns to alternative approaches to incarceration. If we conclude that the prison has indeed become obsolete, with what do we replace them? Where will all of the prisoners — the murderers and the rapists — go? What might that society look like? Given how the prison as an institution is so deeply embedded in our social psyche, the mere idea of abolishing it can seem rather daunting. Davis argues that this is the wrong way to think about such a formidable problem, urging us to think bigger.

“It is true that if we focus myopically on the existing system…it is very hard to imagine a structurally similar system capable of handling such a vast population of lawbreakers. If, however, we shift our attention from the prison, perceived as an isolated institution, to the set of relationships that comprise the prison industrial complex, it may be easier to think about alternatives. In other words, a more complicated framework may yield more options than if we simply attempt to discover a single substitute for the prison system. The first step, then, would be to let go of the desire to discover one single alternative system of punishment that would occupy the same footprint as the prison system.” (p. 106)

In her view, the key to upending the status quo lies in untangling the relationships that cement the PIC as a seemingly permanent fixture of our society. At a minimum, this means divorcing corporate profit from state punishment by reducing reliance on private prisons and removing the economic incentives that make the PIC tick. It also means dislodging the prison from our social consciousness — in short, removing its ever present stamp on our society. It involves cutting the mic of self-seeking politicians, correcting the historical record on crime, and disseminating the facts about US incarceration. And it entails communicating a bold, progressive vision that lends inspiration for the future and seeks to mend what has already been broken.

An unabashed countercultural revolutionary for the better part of her life, Davis isn’t one to soft pedal the radical transformations realizing such a vision will require. To meaningfully confront the epidemic of mass incarceration and usher in a more egalitarian system of justice, she insists we target both ends of the pipeline: not only rolling back many of the wrongheaded legislative decisions of the past forty years, but also addressing the systemic issues that create vacuums for crime.

What might this look like in practice? Eliminating excessive sentencing rules such as mandatory minimums; applying greater pressure to prosecutors and law enforcement with respect to transparency and accountability; formally ending the colossally misconceived war on drugs; shoring up immigrant’s rights and protections for refugees fleeing harsh conditions in their own countries; decriminalizing sex work; and shifting our penal priorities in the direction of rehabilitation, substance abuse prevention, educational reforms, and correcting the pervasive inequality, both economic and racial, that threatens the fabric of US society.

“An abolitionist approach…would require us to imagine a constellation of alternative strategies and institutions, with the ultimate aim of removing the prison from the social and ideological landscapes of our society. In other words, we would not be looking for prisonlike substitutes for the prison, such as house arrest safeguarded by electronic surveillance bracelets. Rather, positing decarceration as our overarching strategy, we would try to envision a continuum of alternatives to imprisonment—demilitarization of schools, revitalization of education at all levels, a health system that provides free physical and mental care to all, and a justice system based on reparation and reconciliation rather than retribution and vengeance.

Alternatives that fail to address racism, male dominance, homophobia, class bias, and other structures of domination will not, in the final analysis, lead to decarceration and will not advance the goal of abolition.” (pp. 107-108)

Davis is careful to note that this doesn’t mean we forsake the needs of the currently incarcerated in our quest for more just horizons. We still must bring an end to the profit motive underlying the unethical practices and outcomes caused by lapses in officer training, understaffing and overcrowding in our prisons, for instance, so long as those institutions persist. The lives and human rights of prisoners will always matter, even as we fight to terminate the conditions and systems that put them there in the first place.

“Radical opposition to the global prison industrial complex sees the antiprison movement as a vital means of expanding the terrain on which the quest for democracy will unfold. This movement is thus antiracist, anticapitalist, antisexist, and antihomophobic. It calls for the abolition of the prison as the dominant mode of punishment but at the same time recognizes the need for genuine solidarity with the millions of men, women, and children who are behind bars. A major challenge of this movement is to do the work that will create more humane, habitable environments for people in prison without bolstering the permanence of the prison system.” (p. 103)

Closing Thoughts

Angela Davis has been on the front lines of the prison abolition and decarceration movements for longer than I’ve been alive. In her careful yet uncompromising book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, Davis presents a compelling case that the prison as an institution intended to solve our social problems is beyond saving. Rather than mitigating the racism, misogyny, toxic masculinity, sexual violence and other constants in our society, Davis says our current system merely hides them away — where they take on a “ghastly vitality behind prison walls” — and renders them less visible to the public eye. She invites us to consider whether carceral approaches to justice are still, or ever were, valid. Does locking more people in cages actually enhance public safety, or, as the evidence suggests, lead to recidivism and accelerate the cycle of poverty and racial inequity?

She further asks us to envision a society no longer in need of prisons. Though this closing section could have been more developed, Davis sprinkles in more than enough ideas and real world examples to jumpstart the conversation. For the United States to embrace sustainable alternatives, we will need to kick our unhealthy obsession with punishment and begin diverting resources away from the prison industrial complex to which we’ve collectively succumbed and toward housing, accessible health care, education, drug treatment programs, and jobs for disadvantaged communities. Perhaps then we will have cultivated a society in which the School and other institutions of promise achieve more cultural resonance than the Prison.

Further reading and resources:

- Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex

- Critical Resistance project

- The 13th

- How We Got to Two Million: How did the Land of the Free become the world’s leading jailer?

- Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020

- The Sentencing Project

- NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet

- Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Statistics

Comments