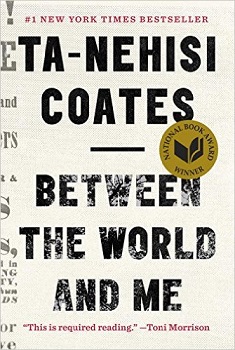

Review: Between the World and Me

“America understands itself as God’s handiwork, but the black body is the clearest evidence that America is the work of men.”

This is not an easy book for white people to read. Nor should it be, because it is not easy for black people to read and learn about their historical travails, much less navigate the same, yet different world in which white and black people, collectively, live out their existence. Coates forcefully articulates the invidious, discriminatory past that has chased and haunted people of darker skin across the ages — a history with great and heavy repercussions which can never truly be atoned for or erased. Too much taken, and too much lost that can never be recovered: lives, livelihoods, memories, culture, possibilities, dignity. America’s is a past with a pulse, one that cuts across demography and state lines, across tax brackets and social strata. And because it is lived by each and every black man, woman, and child in America today, we must never lose sight of it.

Addressed to his adolescent son, Between the World and Me recounts Coates’s story as a youth growing up in Baltimore, his dawning awareness of black-white relations in America, and his personal journey to find peace and enlightenment amid the struggle. Equal parts intellectual and emotional, what he gives to his son is a headstrong portrait of being black in America.

You will hear about his time at Howard University, upon learning that his gifted and charismatic friend was gunned down, sans provocation, by police, with little in the way of justice to follow. You will hear about how what should have been a pleasant night out with his young son in the Upper East Side turned out to be memorable for all of the wrong reasons. You will see the names of Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, John Crawford, Marlene Pinnock, and Tamir Rice — and the echoes of their plights — plastered throughout these pages.

None of this is new. But little of it is acknowledged, and its magnitude understood even less. Coates’s message is not for white people to plead guilty en masse for every problem wracking black communities today, but rather to come to terms with the history that has led us to where we are today and be willing to listen to those whose experiences are not our own. And though we, as white people, may be unable to cognize these experiences directly, we can still be vigilant and considerate of how this history affects their every waking moment and infiltrates nearly all aspects of their lives.

The acknowledgment of the divide before us should come with ease. It is this: the lived-in experience of blacks in Western cultures is not something to which people of white skin have access. Systemic or institutionalized racism is not something white Westerners can mantle for themselves.

“But white people can be poor, too!” cries the disaffected white person unbeknowingly conflating racism with the demographics of poverty. Because, after all, being white and poor is not the same as being black and poor, recalling President Lyndon Johnson’s sentiment from 1965. One cannot correct for or reengineer racist people and racist institutions overnight. The exploitation of the weak by the strong has been a facet of American society dating back to its inception. People in privileged positions, as a function of their race and status owing to this history, have a head start, and traditionally this has excluded black people.

For this and other reasons, we must not do away with the very notion of race. There are two streams of thought found among academic and more mainstream discourse today. One holds that there is no such thing as race: we all are one species (Homo sapiens) that descended from a common ancestor in Africa some two hundred thousand years ago. Race, for this camp, serves only as a token of division, one we are better off without. The other maintains that race has been a persistent feature of human relations throughout our history, and because of this persistence, it is a real phenomenon which helps explain various socioeconomic disparities evident in society.

Wishing the construct of race had never emerged might be an interesting counterfactual thought experiment, but the fact is that it did emerge and thus cannot be ignored given the fallout of its societal penetration. The ontology of race is undeniable; it set people of darker skin on separate trajectories, with vastly different historical outcomes from those of white descent. Hence regardless of whether “whiteness” and “blackness” are constructs with purely social or biological dimensions, the realities they brought forth are self-evident and still manifest in the modern era. They are constructs with consequences. To disacknowledge the palpable inequities racial identity has wrought — or racial identity itself — is to paper over our past and may subvert the project of redress.

Ta-Nehisi Coates was awarded the National Book Award for Nonfiction and the MacArthur Foundation’s Genius Grant for this work, and it’s not difficult to see why. He writes with a raw emotion and effortless profundity that is unparalleled among living writers. As I absorbed his polished prose and clever yet subtle use of metaphor, I was continually brought back to Zora Neale Hurston and her many great literary treasures. And yet absent those things, it is the power of his message that leaves the lasting impression.

Postscript: I highly recommend pairing Coates’s book with his earlier essay, “The Case for Reparations,” which appeared in The Atlantic, as the two complement one another really well. While the former is an autobiography with all the energy of a poetry slam, the latter is more a factual recapitulation of the racist divisions running throughout America’s past. Both articulate, each in their discerning way, why these divisions are deep and irreparable, how they heaped both tangible and intangible harm upon black communities, and why it is the intangibles that make plenary redress impossible. Acknowledgment and avowal of the past may not be enough, but it’s a good start.

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Further reading:

- How Ta-Nehisi Coates’s letter to his son about being black in America became a bestseller

- With Atlantic article on reparations, Ta-Nehisi Coates sees payoff for years of struggle

- Ta-Nehisi Coates and writing about race in America

- Solving the Riddle of Race (Marks 2016); ScienceDirect

Feature image via The Guardian

Comments